31 Aug 2018

[

art

]

On the 16th of May 1967, in the small town of Roubaix, the father figure of the modern chanson bid adieu to the grand stage. A lyrical genius whose influence spread far and wide, touching not only the hearts of millions of Belgians and French, but also inspiring legendary singers such as David Bowie, Jacques Brel produced era-defining music with his thoughtful and theatrical songs, reaching out to a generation of listeners with his beautifully crafted lyrics.

A few years ago, in order to get to grips with the nuances of French and its wide variety of pronunciations and accents, I decided to immerse myself into the francophone culture in order to be better able to pick up on the language’s natural speech patterns.

I decided to start with French music. Given that rhythm is a universal language, I thought it would be relatively easier to acclimatize to a change in the language of lyrics, compared to, say, watching news channels or TV shows. One of the artists that I was fortunate enough to stumble upon was Paul Van Haver – better known by his stage name, Stromae.

At the time, he had established himself as a successful mainstream artist with the help of his debut album Racine Carrée, which followed up on his breakout hit Alors on Danse, a track that torched domestic charts and had a respectable amount of international success, even culminating in a remix by Kanye West that saw many listeners of English music turn their head towards the unorthodox Belgian singer of Rwandan origin.

It was clear from the start that there was something unique about his music. It wasn’t just about this surreal blend of genres – his songs combined the feel-good, envie de danser vibe of electronic music, the purity of acoustic instruments, and melodious vocal harmonies created with the help of his immensely talented group of musicians. However, what really brought his songs together were the lyrics. Melodiously written, yet so strikingly powerful, each of his songs tackled an idea that was truly important – not just singing for the sake of it.

Whether he explores the stereotypes of the male and the female in relationships, the consuming nature of social media, the tragedy of cancer or the importance of a father figure in a child’s upbringing, there is always a tremendous weight behind his lyrics that leaves the listener thinking and always eager to hear more.

There is also this certain dichotomy in his character – off stage, Stromae is quite shy, reserved, playful even, yet when he gets on stage, he has this thrilling, addictive energy – wowing his audience with spontaneous dancing or making them laugh with well-delivered jokes.

What interests me the most about him, however, are the similarities that he has with Jacques Brel, namely in the themes of their lyrics and their live performances.

“I also really admire Jacques Brel – he has been a huge influence on me – but also all sorts of other stuff, Cuban son, and the Congolese rumba which I heard as a child; that music rocked the whole of Africa.”

Brel and Stromae excel in making their audience feel and reflect on their lyrics. This can mainly be attributed to the fact that they don’t shy away from the depressing and controversial. However, how Stromae chooses to deliver these lyrics is interesting to see. While Brel’s instrumentals often mirror the mood of his songs, Stromae almost always uses electronic music as the medium through which he conveys his ideas, giving all of his songs an interesting vibe – they make you want to dance, while also making you think.

In terms of themes, the two have spoken about similar issues – for example, Brel uses the analogy of a Carousel to explore the peaks and troughs of life, while Stromae explores a similar polarity in “Alors on Danse”. In the words of Jamel Debbouze:

A verse that makes you want to die, and a refrain that makes you go wild … a type of verse that makes you want to decapitate yourself, and a refrain that makes you want to have a picnic! Something contradictory, and at the same time, homogeneous.

Their development as artists is also similar. Brel enjoyed a modest amount of success in his early years, but as he grew older, his outlook on the world darkened, and in the 60’s, he cemented himself as one of the headline stars in the francophone world. Stromae began as a struggling rapper, before transitioning to producing, and eventually becoming a complete musician. And the rest, of course, is history.

I stumbled upon both these artists by chance. And yet, the similarities between them have built for me a bridge between generations, while allowing me to view each artist in a different light and understand them better.

Which brings me back to the reason that made me want to listen to French music in the first place – the power that art has in creating links between different time periods, cultures and individuals, and the incredible outlook that someone can get by scrutinizing artists from different time periods. The cliché that “history repeats itself” is only partially applicable to the arts – the same messages can be portrayed through different mediums, leaving a breadcrumb trail through the years that can be retraced. And not only is this worth exploring, it also results in many surprising and interesting findings.

-Chaitanya

Sources

31 Dec 2017

[

football

]

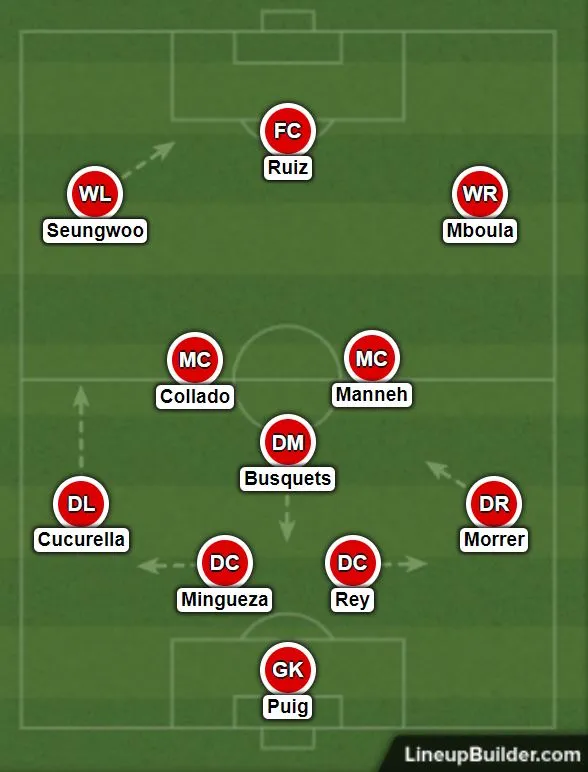

Inspired by Ajax and imbibed with a certain Catalan flavour, the La Masia academy has been a reliable output for FC Barcelona, and over the course of time, has almost become synonymous with it — consistently churning out world-class players such as the likes of Xavi, Iniesta, Busquets, Pique, Puyol, Messi, and many others. The list goes on and on, and Cules always praised their self sufficiency and uncompromising philosophies, citing them as reasons that set them apart from other clubs, which have indeed painted Barca in a brilliant light.

In the past few years, however, promising graduates have been denied access to the first team. Halilovic, Jordi Mboula, Grimaldo, and many others have chosen to change clubs in order to secure a more promising future. Nevertheless, La Masia’s scholars still play an attractive brand of football, inspired by positional play, by combining the principles of their proponents — Johann Cruyff, Pep Guardiola and Juan Manuel Lillo.

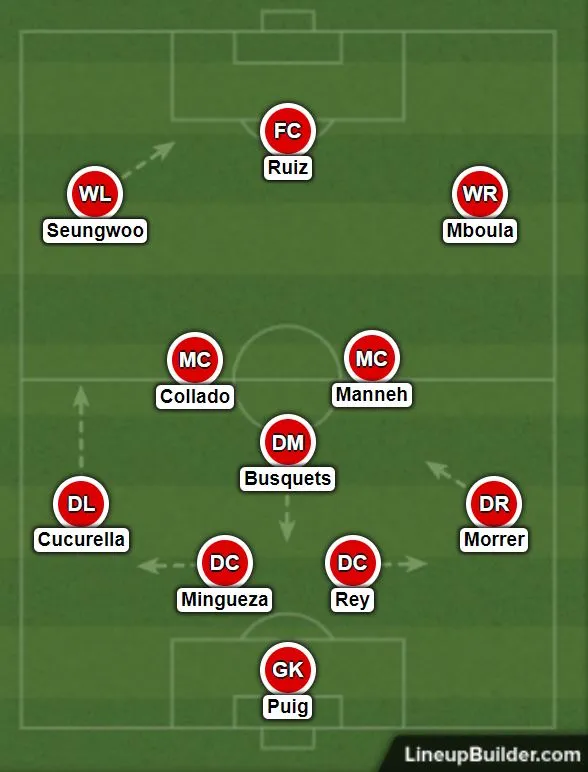

On paper, Barcelona start with a 433. However, that quickly transitions to a more attacking 334. Oriol Busquets plays as a half back, dropping in between Mengueza and Rey to create a back three. The centre backs fan out to the halfspaces, which allows them to be more efficient in buildup when they move forward to the halfway line. Morer moves to fill the position of Busquets, playing as an inverted wing back. Seungwoo plays in a freer role, looking for spaces in between the lines. Cucurella pushes up the field to stretch the field. Collado and Manneh play in the half-spaces, looking to move the ball forward. Mboula plays on the right, as a winger that looks to win 1v1’s and provide the final ball.

Collado can also move forward while attacking to turn the 3–3–4 into a 3–2–5, as shown below:

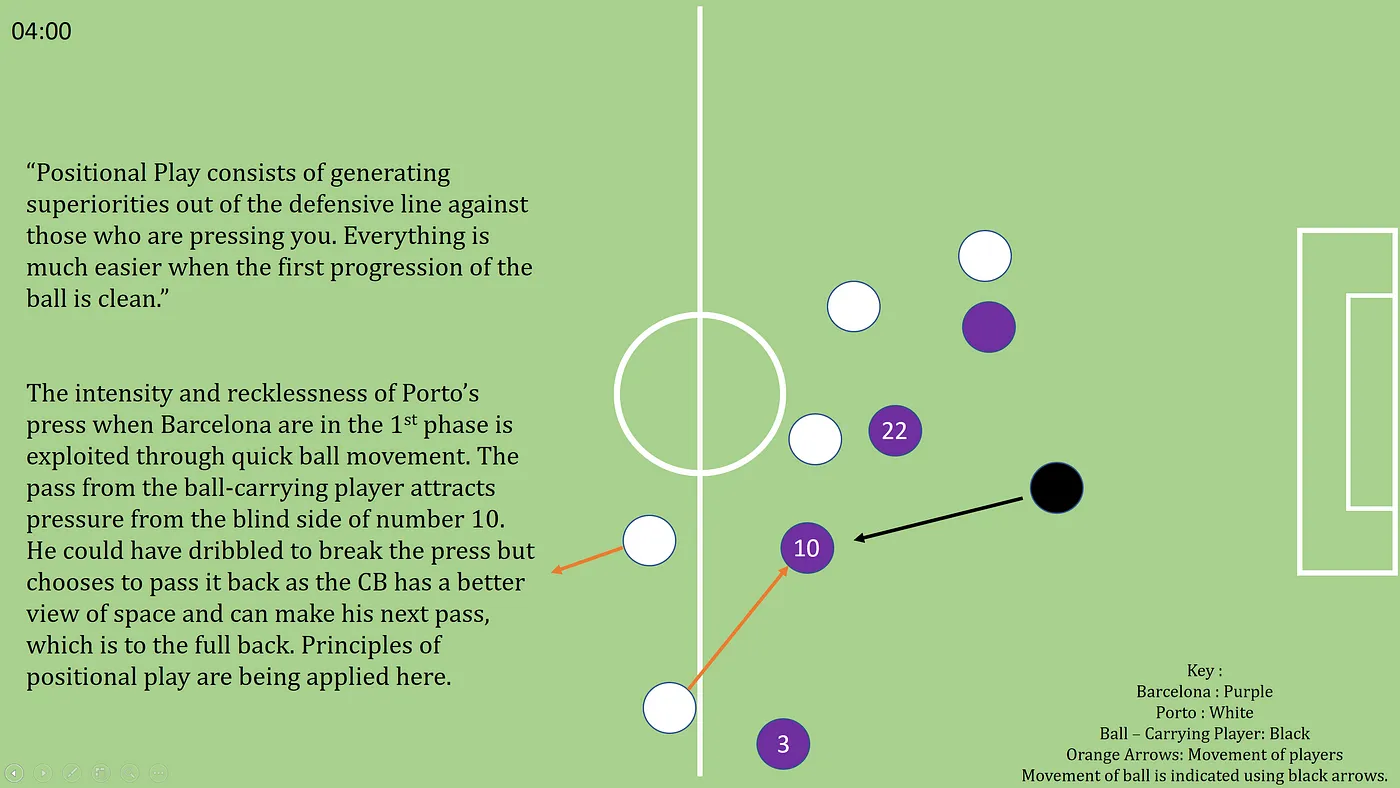

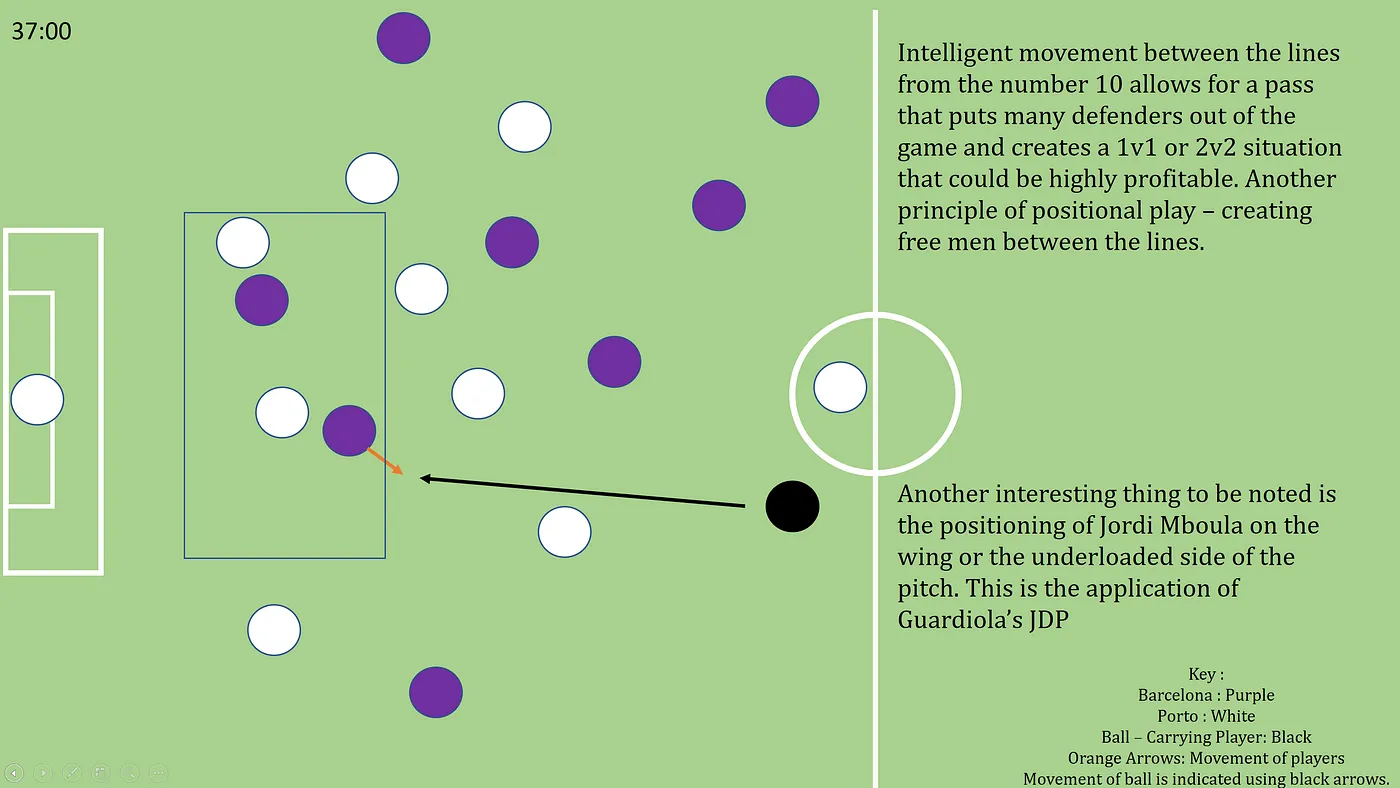

This playing style makes it easier for Barcelona to look for vertical progression, and indeed, that was the main source of their attacking prowess. This allowed them to traverse the pitch effectively, this either drew the press from Porto, which was then used to create space in other places, or place attackers in dangerous positions and create chances.

Throughout the game, Porto’s pressing on the Barca centre backs was very lax. This provided them with incentive to push up and play a high line. This has two benefits — the space between the lines reduces, allowing for more effective counterpressing, and makes it easier for progression between the lines while providing safe options for the midfielders to recycle the play.

Moreover, during goal kicks –Busquets drops into the back two and the centre backs fan out to play wide, to create a numerical advantage.

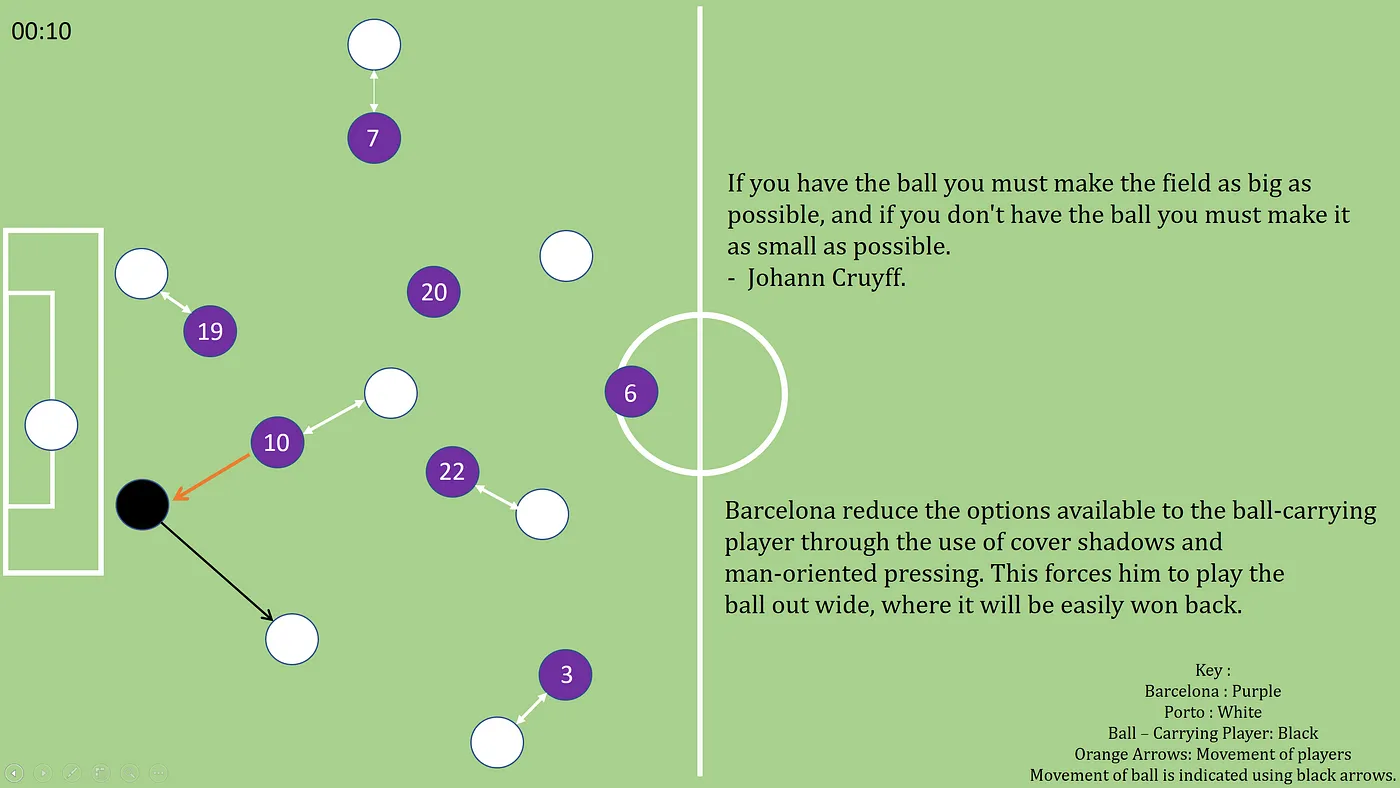

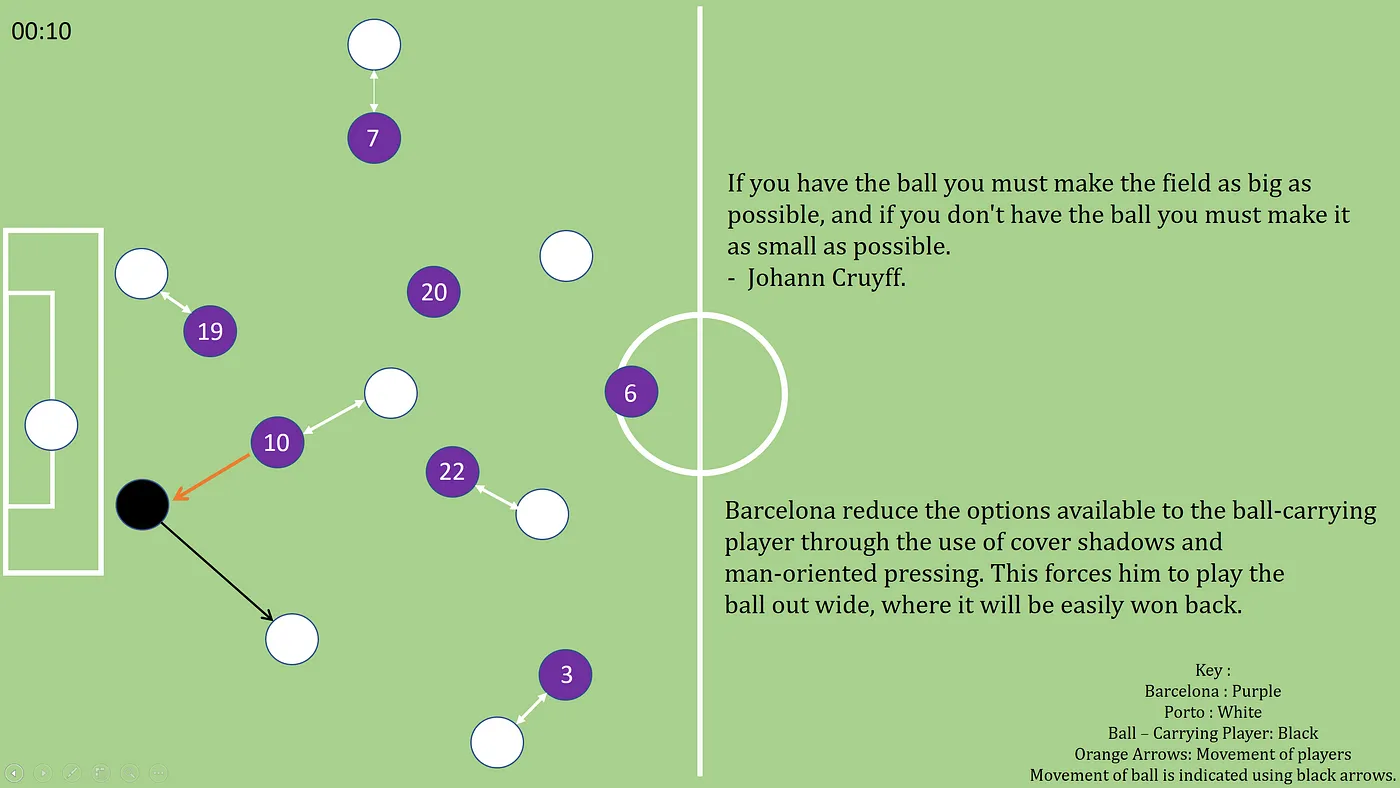

When you have the ball, you must make the pitch as wide as possible, and when you don’t, make it as small as possible

Aggressive counterpressing when the ball is lost makes the pitch smaller for the opponent by preventing vertical progression. The ball is often also forced out wide, where it is easier to win the ball back.

The close distance between the lines of the Barcelona players also helps them in this. After winning the ball back, especially in the midfield areas, Barcelona tend to play the ball to their centre backs. This buys them time for the other players to get into position, as their pressing has the tendency to unravel their structure. Theoretically, this is more efficient compared to looking for the pass after winning the ball back, as the player is out of position and therefore does not have a good view of the pitch. Physically speaking, this also allows the players to recuperate. The intelligence and vision of the centre backs (and Busquets) allows the team to hunt for spaces, and gives them confidence in finding spaces between the lines during buildup. This is best exemplified by the ever present space-hunting of Lee Seungwoo.

It is also important to note that while FC Porto have goal kicks, Barca also force their goalkeeper to pump the ball up, instead of allowing them to play it short. The striker and wingers closely mark the centrebacks, who push inside.

Movement Between the Lines, Third Man and Blind — Side Runs

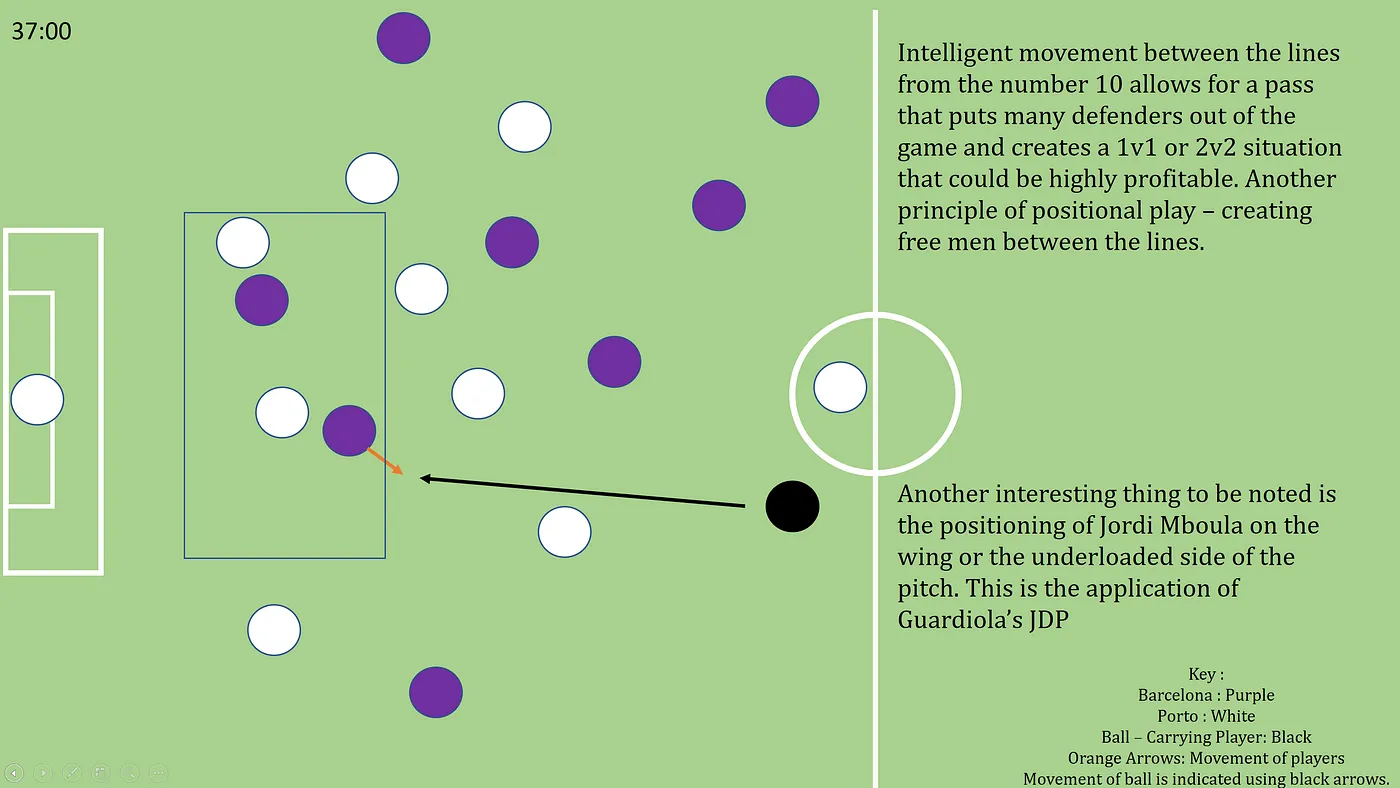

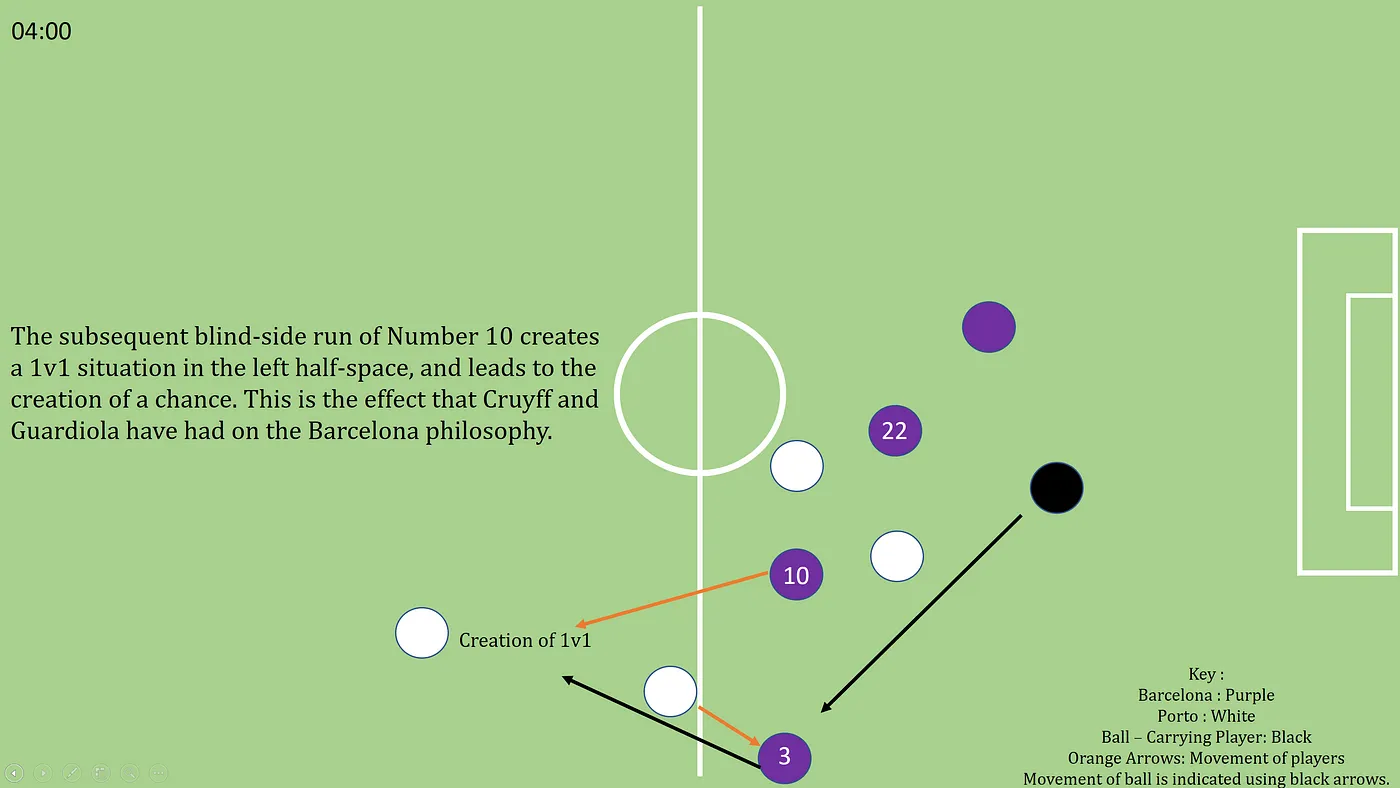

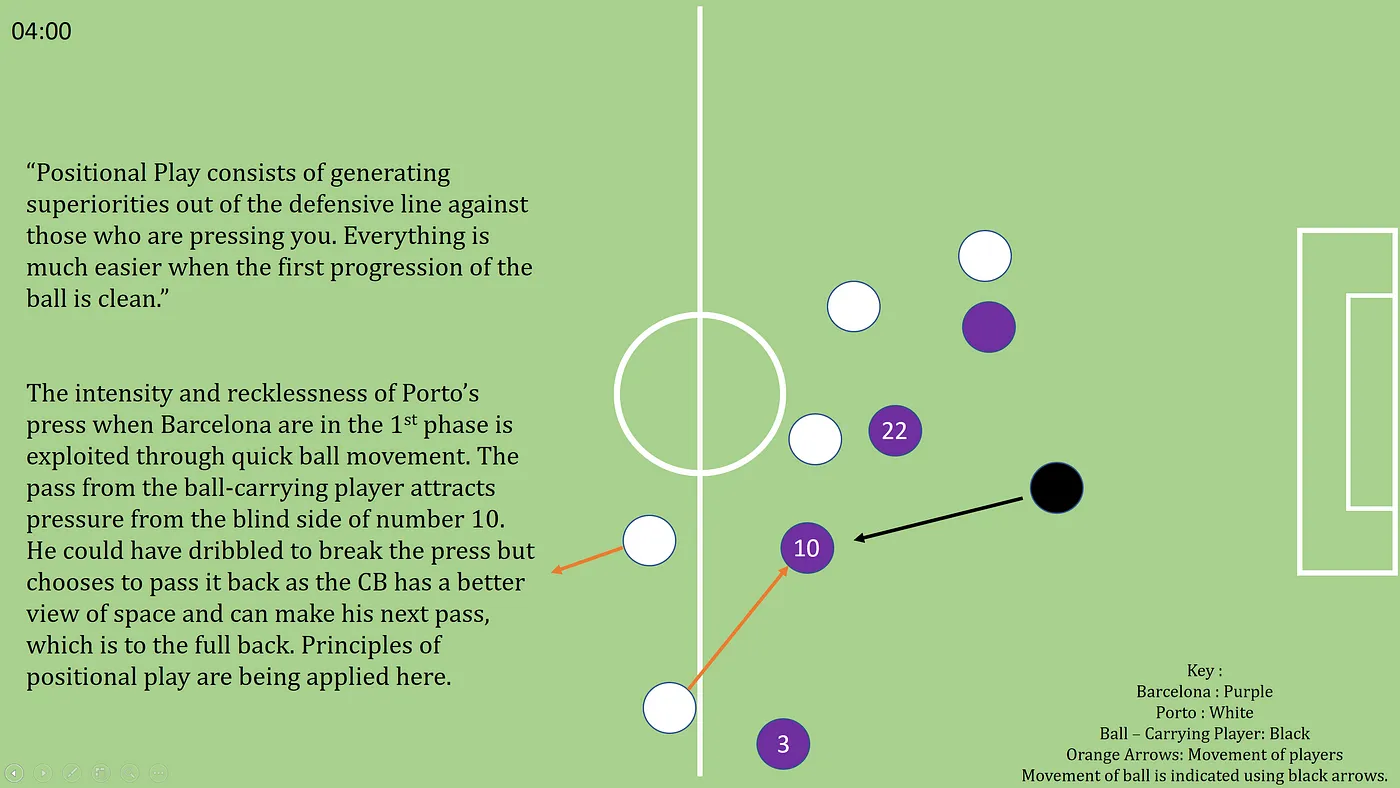

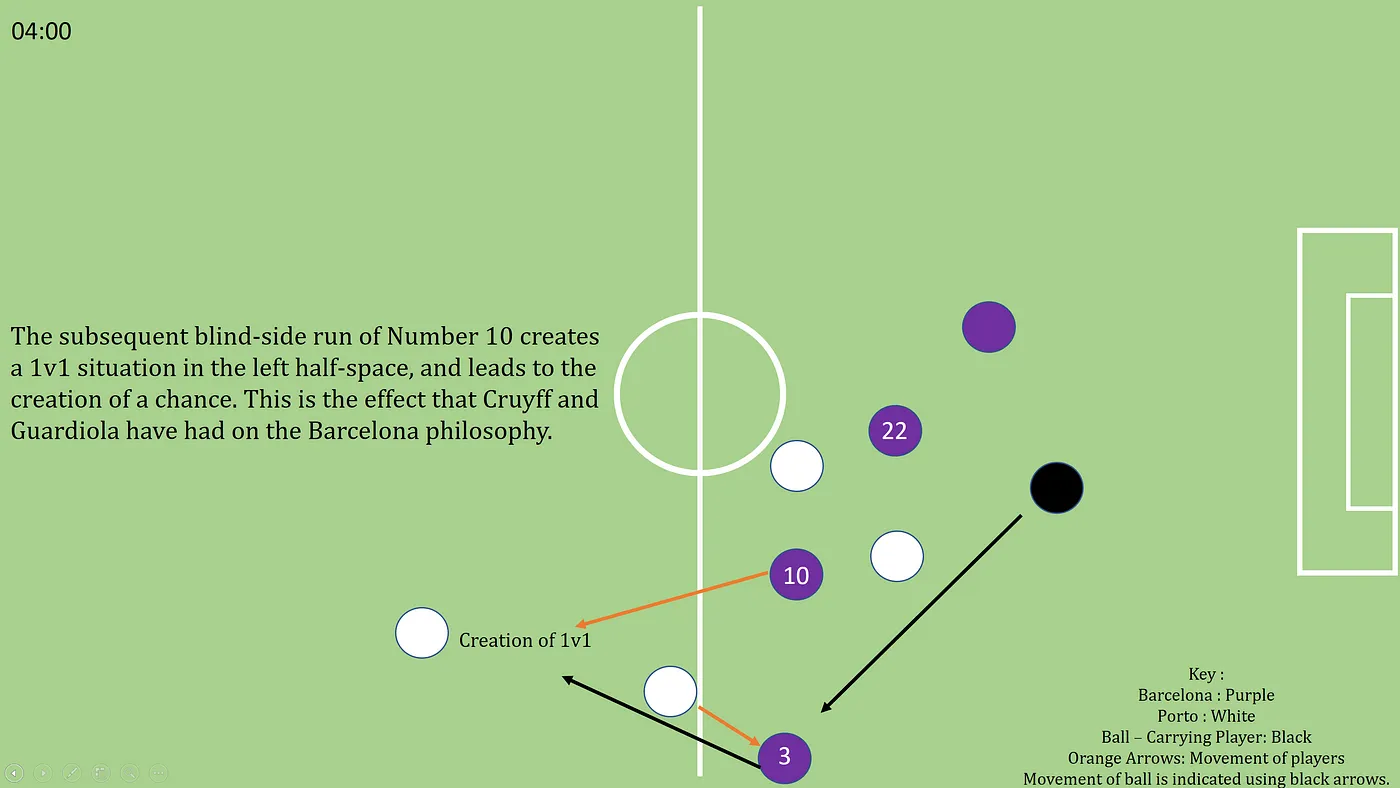

Barcelona seek to progress the ball using between-the-line runs, blind side runs, and third man runs. Notably, they often use a combination of the third man and the blind side to devastating effect.

A notable example of this, early in the game, showcased how Barca could easily dismantle FC Porto’s press, and to devastating effect. While it was earlier noted that the centre backs were not pressured much with the ball, the players closest to them were pressed quickly. In this case, Seungwoo drops deep to receive the ball and is immediately pressured by the right back of FC Porto. This press was easy enough to dribble against, but, as previously mentioned, he does not possess the necessary vision required for efficient movement of the ball. Therefore, he passes it back, and the CB picks out Cucurealla who is now in an open position, which subsequently draws pressure. Seungwoo makes a blind side run that leads to a 1v1 situation, which he eventually wins.

Another interesting way the free man is used is on the underloaded side of the pitch, which is another principle of JDP. In this case, Jordi Mboula, on the right, serves to play in that position, with his pace and skill. He was given the ball in a few good positions at times, however, for the most part, he failed t beat his man during crucial 1v1’s and provide the crucial final ball. Furthermore, Porto had gotten wise to the tactic and at the start of the second half, two players were constantly occupying the right side of the pitch — which removed the qualitative superiority of Mboula and replaced it with numerical superiority in favour of Porto. This disincentivized Barcelona to switch the play. However, Porto were not the only side to make tactical changes at half time.

To counter the aforementioned move, Dani Morer began to play as a more conventional right back, overlapping and accompanying Mboula on his ventures forward. Busquets took his place as a deep-lying playmaker. This was because the Porto players used cover shadows to prevent him from getting the ball when he played as an inverted full back.

Despite Barcelona’s impressive tactical flexibility, they still have room to improve, especially when it comes to their defending and chance creation. While they can work the ball well, they find it difficult to create chances or shots from dangerous areas. A good example of this is the runs of Ruiz, who has proficiency in making diagonal runs, but these same runs drag him away from the goal, and prevent him from getting a dangerous shot off. Seungwoo’s space hunting also leads him into what I would call “inefficient” areas of the pitch.

Furthermore, Barcelona’s first goal was a ruthless showing of the weakness of their defensive setup. In the build up to the goal, we can see that Collado didn’t pressure Porto’s Cassama quick enough, despite the fact that he was near the edge of the penalty box and had enough time and space to make a dangerous action. The defender covering the goal scorer, Bruno Costa, was unaware of his movements, as his eyes were on Cassama. Lastly, despite the fact that Collado saw the run of Bruno Costa, he didn’t have the awareness to move ahead and play him offside.

In conclusion, Barcelona B’s playing style is aesthetically pleasing. However, it can be made more effective, and in terms of defending, the La Masia graduates should exercise more pragmatism.